The Extraction

Daniel needed an inexpensive dentist. “I have this tooth that throbs,” he told another semi-artist like himself; both were trying to make their ways in Brussels, “but I don’t have lots of money—between gigs now for six months—no health insurance. So if you know of anyone…” Daniel pointed to his cheek, where, just underneath, something rotted, pulsated, hurt. He touched the spot tenderly.

A couple of days later, a telephone call came from this semi-artist acquaintance: “A friend of mine says he’s heard of a dentist but doesn’t know if he’s any good, but he’s supposed to be cheap.”

“The pain’s worse. Give me the contacts…”

Daniel got the dentist’s answering machine four times over three days until a real voice came on.

“Hello?”

“Am I…sorry, are you the dentist? Do you speak English?”

“Yes. Who is this?”

“My name is Daniel. I am an American living here but my French and Flemish isn’t so—”

“I understand. How can I help you, please?”

“I have a toothache, and someone gave me your name.”

“Ah. Who?”

“I don’t know. An acquaintance of a friend. Listen, I have a tooth that’s killing me but I don’t have a lot of money, I’m not in the Belgium social services yet because I’m still not a resident due to—”

“I understand what you are saying. You want an appointment?”

“Yes. Sooner the better.”

“Tomorrow?”

“Tomorrow’s Saturday.”

“Your toothache takes holidays on weekends?”

“No.”

“So?”

“Okay.”

“Ten-thirty in the morning is good for you?”

“That’s early.”

“That’s what I have available.”

*

Daniel turned into a narrow street in an old building and found the dentist’s name on a faded fake bronze plaque with a letter missing, chipped at the corner, and over time rain had stained it. He rang and was buzzed in. A sign pointed to a waiting room where Daniel sat alone on a rickety wooden chair whose slats wiggled in place. The pale walls had probably needed a good lick of paint about ten years ago. He didn’t hear anything going on in the next room behind the closed door. No buzzing or doctor-patient mumbling.

The waiting gave him a bad moment to consider his mother dying back in the USA. Once a month he tried to scrape together enough money to telephone her. Sometimes it was a choice between a couple of apples, coffee and bread or a five minute effort to understand his mumbling mother miles and eons away in some newfangled rest home in a bed, half out of it. He would have preferred to email her, but she was in a hospital now, and email wasn’t an option. She was dying of old age and neglect and being without love; she had mumbled as much to him last time on the phone before hanging up.

“You are Daniel?”

The door had opened and light had shot in and there was the dentist.

*

The dentist’s chair Daniel was asked to sit in seemed like a real dentist’s chair with no wobbly slats. It looked and smelled mostly like a dentist’s office—some metal cabinets, a plate of dentist instruments—but looking to his right, there was a second room framed by an arch which was more like a living room with a big bookcase, a large desk, a sofa, couple of easy chairs, a rug, lamps, like a home. Daniel sat expectantly with a paper bib fastened around his neck on his chest watching the dentist set-up.

The dentist seemed to be somewhere in his fifties, maybe more, looking a bit grey like the building, and as he puttered about, he would glance at Daniel with a smile seemingly intended to create some patient-dentist empathy and trust, but the smile held no warmth, and seemed a bit of a strain for him. These smiles made Daniel uneasy and a little tension wiggled up his backbone and took root. It made him think of the little smiles he made into the telephone when he listened to his mother babbling and breathing and listing her problems, and he would smile into the telephone, without hope or an idea of providing some relief. He listened because he was her son, she was his mother, death and a sea were between them, and it was the very least he could do.

The dentist said, “What’s the problem again?”

“I have a pain.”

“Where?”

“In there.” Daniel gestured inside his mouth, toward the back, on the right, a molar.

The dentist gazed steadily at Daniel, measuring. A genuine smile twitched, briefly, over his lips, gone like lighting, something decided in that instant. “Well then, if the pain is in your mouth, perhaps you are sitting in the right chair.”

*

The dentist finished setting up the tray with sharp delving instruments; there was no nurse to help out, to distract Daniel with breasts under a stretched taunt blouse, or a face with a gentle, assuring look. Daniel watched the dentist’s moves; he thought he caught tremors rolling over the fingers. The dentist did not wash his hands, but snapped on some plastic gloves.

“Okay. Now…just one moment.”

Daniel watched the dentist walk to the other room, take up the phone on the big wooden desk with his gloves on and light up a cigarette. The dentist dialled a number, took two puffs, then muttered several sentences into the receiver, then hung up and returned, leaving the cigarette behind in an ashtray generating slow smoke signals.

“Let’s have a look.”

“I haven’t had a check-up in a long time.”

“How long?”

“A long time.”

“Well, we’ll have a look.”

“But I can only afford some work, not a lot.”

“We’ll do what’s necessary within your budget restrictions.”

“Thanks.”

“Anything else, more questions?”

“No, sorry, go on.”

The dentist turned on the harsh oblong light suspended above his head, shoved it close to Daniel’s face, laid a single finger on his chin, and Daniel obediently dropped open his jaw.

The dentist went in.

*

The dentist smelt like cigarette smoke. Breathing right into his face. With a long silver hook he started poking at the bottom right molars and methodically worked his way around the semi-circle of Daniel’s jaw, jabbing at each tooth in succession, as though knocking on small closed doors, as though trying to pick locks on others. The dentist’s smoky smell reminded him of his mother’s smoky mouth. Sixty years or more of filtered and non-filtered cigarettes had turned her lungs into harsh coughing apparatuses, her teeth brown and weak and one after the other slipping out like reluctant leaves on a mouldering old elm tree with its own disease no one could cure; at last count she had maybe three, at most four, of her own teeth left. “Can’t chew things,” she told him over the telephone. “Suck things through straws. Suck mush.”

“That’s real tough, mom,” Daniel replied.

“I like food.”

“I know.”

“It’s all I have left.”

“I know.” All he wanted to do was hang up.

*

“You have an American mouth.”

Daniel was surprised. He expected bad news. Or maybe this was bad news. “I do?”

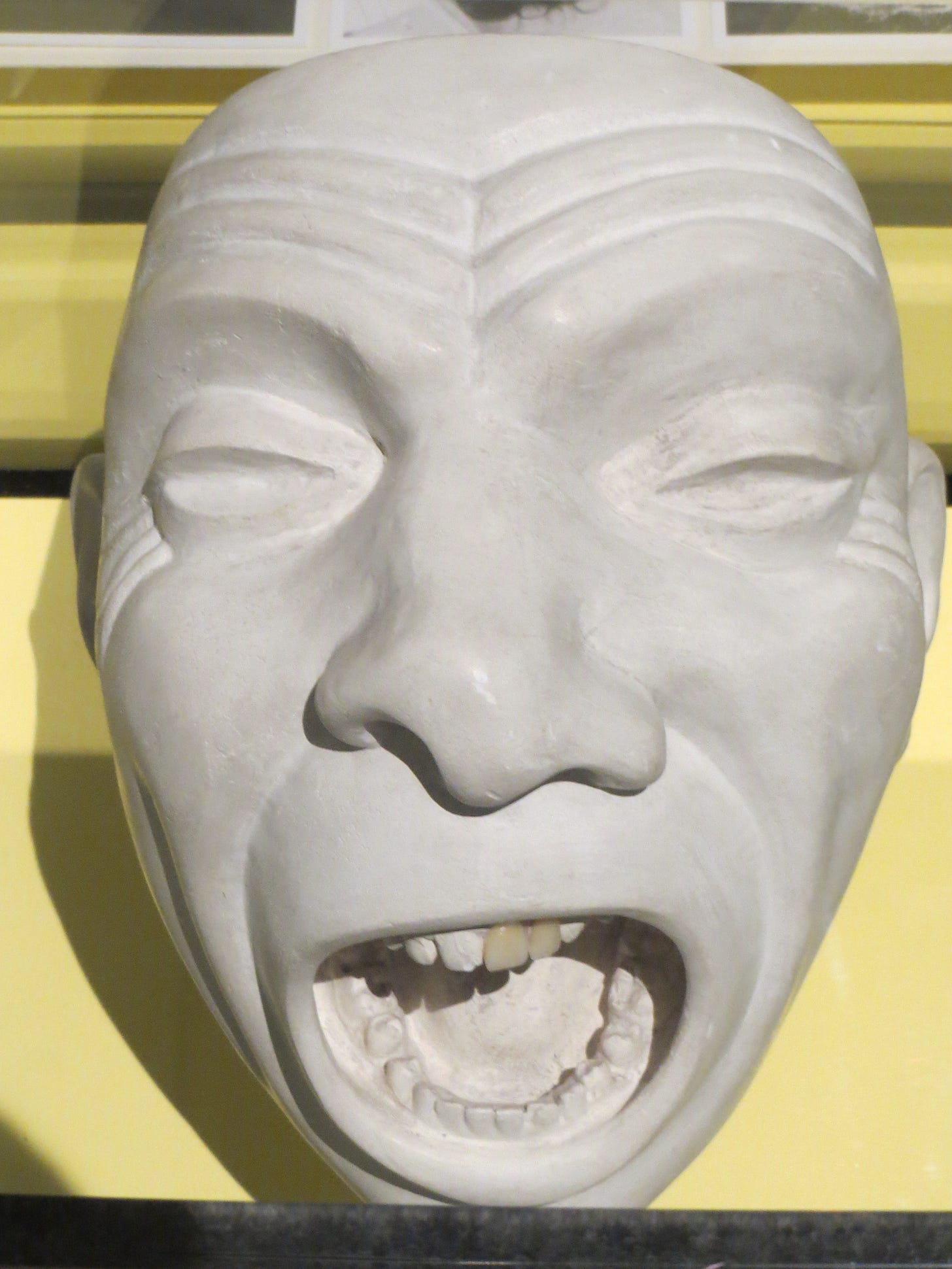

“They teach you early in America. How to brush. How to take care. Here, Belgium, very bad. Non existent. I have seen some truly awful mouths. I have looked into catastrophes. People who have not brushed their teeth for years, if ever. More black than white. Things wiggling around in there, living in caves. Thriving. But your mouth. Your mouth is a pleasure. I see only three cavities.”

“Three?”

“One big, two small. I found some decay inside the large one in the back, a molar. Downstairs one on right. This large one we better take care of. The other two can wait.”

“Will you have to take any of them out?” He didn’t want to start being toothless like his mother already.

“No, no.” The dentist gazed again at Daniel, lingeringly and inquiringly this time. Once again, he tapped the jaw open, went in with the same crooked, pointed instrument and gently prodded at the cavity “downstairs,” lifting Daniel half out of the seat with the sudden sharp piercing pain that took his breath away.

The dentist quickly removed his instrument. “See? Painful, no?”

Daniel was afraid there were tears in his eyes. He nodded quickly, once, twice.

“How long have you been in this pain?”

Daniel told him, “It just started hurting. Like recently.” It had been longer, but didn’t want to appear foolish for letting the decay go on so long.

“We can do a filling.” The dentist looked at Daniel. “But you made me understand you don’t have much money, correct?”

“Hmm.”

“You are not on the Belgium mutualité, the social insurance—”

“No, no. I’ve never had an official job here. Don’t qualify. Yet.”

“Well…we can perform this without using Novocain.”

Daniel, his head clearing as the incredible waves of pain diminished back to the rear of his mouth from where it had burst forth, spoke to make sure he had heard clearly, “You mean, you wouldn’t deaden it?”

“You want to save a little money here, a little money there?”

“Yes, I guess….”

“Then I save you a little money. I will do a little drilling, and then we take a break, then drill some again, a break again, and so on, until it is finished. That is the only expense I can eliminate. It is a small one, but…if as you say you have little money….”

“But it will hurt.”

“Well, there may be some discomfort. Drilling without anaesthetics… Here’s what we do. When you feel too much pain, you raise your right hand, I will stop, and we will take a break. From your pain.”

Daniel thought briefly about the implications. Considered his alternatives. Mooted whether just to slide out of the chair under the cloak of “wanting to think about it.” But then just nodded, accepting. He wanted the pain to go away.

*

The pain brought Daniel into another universe of sensation he had, till then, only read about in books, seen in movies, but had never believed possible as a personal experience. Repeatedly, the dentist took the drill, lowered it in, whirled it on, and the noise accelerated several octaves as it went up against the tooth, and then all inner hell broke loose as a pain shot through his neck, deep into his cranium, twitching every muscle a s Daniel’s buttocks and fingers tightened, his neck tendons tensed, until he believed they would burst out of his flesh and swing around, his wild broken hoses, bloodying everything. He arched his back, his right hand shot up. The dentist released the button on the drill and the murderous sound of the drill’s noises diminished, and was being withdrawn.

“Okay, we will take a breather. You Americans say that, a breather?”

Daniel made a pathetic bleating sound weak in this throat, not up at that moment to confirm the dentist’s handle on Americanisms.

The dentist hung up his drilling tool on a round hook-like object and it dangled there as though some sort of trapeze on high wires, swaying. He walked to the other side of the room, picked up the same telephone as before and dialled while lighting another cigarette and mumbled further brief urgent somethings into the telephone while Daniel felt his whole body vibrating as though he was a tuning fork forcefully struck.

*

“It hurts,” his mother liked to tell him.

“The illness?” he asked her.

“No,” she answered. “The illness is nothing. Dying, nothing. That is a relief. It’s being alone. Doing it alone. That’s the hurt.”

“I’m sorry mother,” Daniel would say back. Then he would lower his voice. “I can’t hear you. The connection is bad.” Knowing she probably did not have enough strength to repeat what she had said.

*

The dentist was back at his side. “Okay? Continue?”

Daniel swallowed long and deeply before nodding his head once.

The dentist’s finger touched his chin, the jaw now reluctantly coming slowly open, the drill kick started, the dentist, without a mask, with cool resolve, brought it inside, applied the pressure.

Daniel tried to study the dentist’s face instead of concentrating on his own state. He could surreptitiously look from the dentist’s eyes that were intently focused on his task, and roam the face. The dentist had shaven clumsily. There were a few stray hairs appearing out of the nose. The skin was bad from too many years of smoke and maybe looking at awful Belgium mouths. The overwhelming close-up of this face scared him, so his eyes returned to the dentist’s eyes staring inside him, and then a nerve was hit, squarely.

*

It was when the dentist came back from his fifth break that Daniel had made his decision.

“I can’t take it any more.”

The dentist’s face took on a despondent look. “But it’s nearly over.”

“It’s too much pain.”

“But it’s—”

“I can’t do this.” Daniel wondered whether that had come out a bit whiny.

“Well,” the dentist explained calmly, “we can’t leave the tooth open like that. Putting the filling in it now with some of the decay left in there, as there still is, no, you’ll get an abscess, the whole mouth could become infected, your brain stem is close by. I don’t want to alarm you, but…we must finish the job.”

“I can’t.”

“You’ve been brave so far. A brave fellow.”

“I’m not any more.”

“I see. So then. Your nerve is exposed. What do you suggest?”

His mother, Daniel knew, unlike him, had no options. There was nothing to do for old age in a strange bed treated by unfamiliar people and no visits, day after day, stretching to weeks and months, as her time on earth came to its slow, lonely finish.

“Extract it,” Daniel mumbled, imitating his mother.

“What?” The dentist leaned down, not catching the words.

“Take it out.”

“But it’s a perfectly good tooth, and once I do the repair work…”

Daniel looked at him. “Take the pain out.”

The dentist stood back. Calculations were clearly going on as the eyes narrowed, the chin slowly rose.

“I see. One minute. Let me consider.”

The dentist walked back to his other room, took up one of a number of smouldering cigarettes in the ashtray, made another telephone call, talked with agitation, giving occasional glances at Daniel, as though he might be conferring with someone on this case. Daniel could hear nothing; the dentist murmured in quick French, and puffed, smoking nearly most of one cigarette this time. Then hung up. And turned to Daniel, taking another a last, deep drag, then aimed the cigarette’s bright, red dot downward and pushed it into the ashtray and turned it hard, left, then right, repeating the gestures three quick times, breaking the remaining length with the pressure. Then looked back up.

He returned.

“Okay. I understand you. You insist.”

“What do you understand?”

The dentist steadily—Daniel thought maybe even kindly—stared into his eyes, pain-giver to pain-taker, acknowledging that something necessary in his patient’s purpose other than a bad tooth had been deciphered.

“Novocain, not expensive. But you cannot afford. You prefer the pain. Over and over, you take the pain. I wouldn’t say you like the pain, but somehow you welcome it.”

“It’s not like tha—”

“We all have pains. I have ex-wives, ungrateful children, unhappy patients, colleagues and unions and insurance agents, I must call them, tell them, stop with the pain they are giving me. Saturday is the day of the week I always put aside for doing this sort of work, making these calls. Normally, that’s all I do today, and it takes a full day. But you needed my help. I fit you in. How perfectly you would fit into my Saturday, I had no idea.”

“I don’t know what you’re—”

“It’s okay. An extraction will rip the pain out of your mouth, is quicker, but has the added benefit that it will leave you with some pain for a few days and I am sure you do not want, or cannot afford, pills for pain so I will not prescribe any, yes? I say once more, I do not recommend this procedure, but if you insist….”

“I insist.”

“As I thought you would.” The dentist made a very minor, half-hearted shrug—“A pity” — and turned to his tray of instruments and devices and alternatives to degrees of pain. He selected his instrument.

“Ready?”

“Take it out.”

The dentist gripped what looked like thin elegant pliers and with little warning jammed open Daniel’s mouth and, with cigarette breath like his mother’s panting on his face, went in for the kill.

And for the next minutes and seconds of wrestling and sounds and through the days that followed, Daniel had no other thought in his mind except his own damned throbbing red pain.